I interviewed Christian Cardon de Lichtbuer on January 31, 2024, on his last day as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Chief Protection Officer. My interest in this conversation stemmed from my research at the ICRC’s archive on this institution’s involvement in the Palestinian refugee camps in the immediate aftermath of the 1948 war in Palestine (known in Israel as the War of Independence, and as the Nakba, or catastrophe, in Palestinian collective memory). I had just finished my six-year-long ERC-funded project on the history of medicine in the Middle East at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and this Sabbatical year in Geneva was supposed to be my time to reflect on my research, finish up a couple of projects, and decide what to do next. We arrived in Geneva in late September 2023. As events unfolded back home in the months to come, I found myself absorbed in this particular project, concentrating on 1949–1950. I read thousands of ICRC documents alongside the historical Palestinian press on the formation of the refugee camps in what would become the West Bank of the State of Jordan, but was, in 1949, still known as “Arab Palestine”. My understanding of my sources and my reading of the news kept feeding each other, leading to my conversation with Christian Cardon, published in Hebrew at the beginning of February 2024.1

During the 1948 war, about 800,000 Palestinians were compelled to leave their homes in territories that became part of the state of Israel, and they were not allowed to return. This refugee problem was never solved, remained one of the sore points of Palestinian-Israeli relations, and had ramifications in the entire region. In late 1948, however, the problem was acute and required immediate solutions. Hundreds of thousands lost their homes and most or all of their possessions. The refugees needed shelter, food, and medical care. They also needed a long-term political solution, but from the perspective of the United Nations and humanitarian organizations, immediate assistance was crucial to prevent mass starvation and the spread of epidemic diseases to the entire Middle East.2 Water- and insect-borne epidemic outbreaks do not immediately come to mind when we think of present-day conditions – but in 1948, the risk of typhus, smallpox, and even cholera was fresh in collective memory.

The comparison between the war on Gaza and 1948 is compelling. Both Israelis and Palestinians use the term “a second Nakba” for present-day events, given the mass scale of destruction and the sheer number of individuals forced to leave their homes.3 From the perspective of a historian of medicine and public health, however, the immediate human cost of the current war is far greater than in 1948. The number of direct war casualties has surpassed that of 1948 already in late 2023. Unlike 1948, moreover, the situation of displaced persons is further exacerbated by the continuation of an active state of war in their places of refuge. Both Israel and Egypt blocked their border with the Gaza Strip, and civilians are incapable of leaving for safety.4 The ongoing war also substantially limited the ability to provide humanitarian assistance. Before proceeding to my interview with Christian Cardon, I would like to outline those differences as well as some similarities and thus frame a historian’s perspective on the current human conditions.

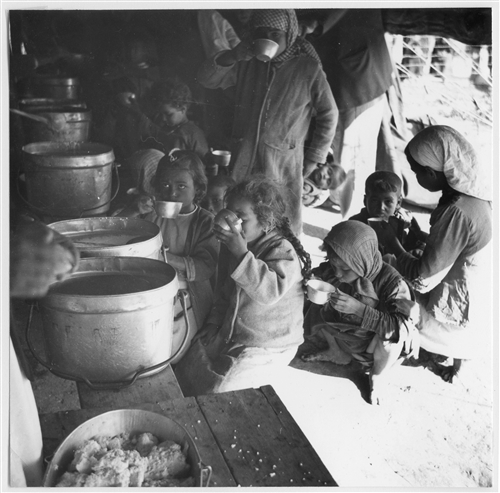

The starting point for this comparison is the space in which refugees found refuge. In 1948, they were spread in those territories of Palestine that did not become Israel – and would later be named the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, as well as the neighboring Arab countries – mainly Lebanon and Jordan, and to a lesser extent, Syria and Egypt. Until the arrival of humanitarian organizations in late 1948 and early 1949, they found different kinds of temporary accommodation. Some could afford to rent an apartment – but their resources were dwindling quickly. Some stayed with family members, but families’ generosity and resources were limited as well. Some found shelter in public buildings such as mosques or schools – but these had to resume operation at some point. Most refugees, by early 1949, lived in the open – in makeshift tents, under trees, or under the open sky; some found shelter in caves – with very little to shield them from the winter’s cold.5

In early 2024, almost two million were crowding in Rafah, a territory that used to be the home of about a tenth of this number, an area that continues to constitute an active war zone. People who left their homes in late 2023 and early 2024 thus did not leave for safety. Their only shelter is makeshift tents or the open sky. The crowdedness of the space, moreover, produces hunger and epidemic dangers, the kind of danger that humanitarian organizations had feared in 1949 and managed to contain at the time. The fact that the civilian population is prevented from leaving the Gaza Strip either to Israel or to Egypt makes today’s situation much more dire.

Beginning in January 1949, and funded by the United Nations Relief for Palestine Refugees, the ICRC, the League of Red Cross Societies, and the American Friends Service Committee jointly provided immediate relief, which operated on three levels – epidemic prevention, food provision, and health services.6 None of these are available today in Gaza, increasing the morbidity and mortality rates far beyond the more immediate war casualties. One of the objectives in the construction of refugee camps in 1949 was epidemic control. The camps were regularly dusted with DDT, which had severe long-term environmental and health consequences. However, such regular pesticide usage managed to prevent the spread of insect-borne epidemics such as typhus, trachoma, and malaria in the short run. Arab governments and WHO personnel also vaccinated refugees against tuberculosis and typhus. Localized outbreaks were contained through limited quarantines. These anti-epidemic measures were the most successful aspect of the initial humanitarian intervention. Given the refugees’ rudimentary living conditions and grave concern about region-wide epidemics, this was indeed a success.7

Many epidemics that international organizations feared in 1949 are preventable or treatable seventy-five years later. Moreover, they are relatively rare today because sanitary infrastructure and clean, drinkable water have made most insect- and water-borne diseases a thing of the past. Both water and sanitary systems in Gaza were, however, severely damaged, and in most refugees’ concentrations, they are virtually non-existent. The possibility of prevention is minimal, and treatment is impossible. The result, in the winter months, was mainly water-borne diseases of the digestive system, which can be fatal for babies and infants.8 The summer is likely to lead to an increase in insect-borne diseases.

As for food, in 1949, starvation was a real risk for people who lost their means of livelihood, and humanitarian organizations distributed food – mainly flour – to almost 900,000 people, most of them refugees. In addition, UNICEF funded the distribution of milk to children under 15. This diet, low in proteins and vitamins, created nutritional deficiencies by late 1949 but kept the refugees alive. Considering that everyone involved believed this solution to be temporary, a carbohydrate-based daily 1,500-calorie diet seemed reasonable as a short-term solution.9 As Cardon states in the interview, the importation of food to the Gaza Strip had been cut sharply since October 7, 2023, and the situation has only worsened since we spoke. In our conversation in late January 2024, Cardon mentioned families resorting to animal food. More than five months later, the toll hunger inflicted on the civilian population has increased even more. The extent of death and long-term nutritional deficits is yet unknown.

In 1949, most medical facilities from Mandate Palestine – in Haifa, Jaffa, and West Jerusalem – remained in Israel. Medication and medical equipment likewise stayed beyond the border. Most Palestinian doctors worked either in private practice or for the British Mandate Department of Health, which no longer existed and was paying no salaries. The Jordanian, Egyptian, and Lebanese governments provided some assistance, but the population’s needs surpassed the capacity of existing hospitals and medical services. Therefore, the ICRC, for example, took an active role in creating the medical infrastructure of the West Bank – supplying medication, trained medical personnel, and funding for hospital operations. In 1949, eight hospitals were built or expanded in the West Bank with active ICRC assistance and made hundreds of hospital beds available to refugees. In addition, refugee camps had small clinics treating routine illnesses and they participated in epidemic prevention.10

On January 31, 2024, only three out of 36 hospitals were functioning in Gaza – and most have been completely or partially destroyed. The operation of hospitals was severely disturbed by a lack of electricity and medication, by direct fighting, and attacks on hospitals and medical personnel. Hospitals that do operate concentrate on emergency war casualties and are unable to treat the sick and chronically ill – including cancer patients, diabetics, and those suffering from heart conditions. Routine medical care for people unable to reach hospitals is virtually non-existent. Given the lack of routine medical attention and medication, the survival rate among the chronically ill is likely to be low.11

The interview below brought together two historical moments – 1949–50 and 2023–24. My historical research in the ICRC archives in Geneva and events unfolding back home triggered my questions to Cardon. His answers had an Israeli audience in mind. Israeli public opinion, during the first months of the war, accused the ICRC of not insisting on seeing the Israeli hostages and not advocating for their release. The ICRC’s involvement in the release of hostages in late November further infuriated Israeli public opinion that believed the organization could use its neutrality to exert more pressure for hostages’ release.12 It was, therefore, important to Cardon to clarify the meaning of the ICRC’s strategic neutrality and moral commitment to human wellbeing. Consequently, his answers convey an understanding of pain and loss on both sides. They also convey faith in Israeli society and its ability to acknowledge the cost of the war on human life. Most of all, our conversation is a plea to acknowledge our common humanity in an increasingly polarized world.

Since our conversation, no other hostages and prisoner exchanges took place. According to estimates, some of the hostages have been killed, either by Hamas or by Israeli attacks.13 In addition, since October 7, Israel stopped ICRC visits to all Palestinian prisoners and detainees. Thousands of Palestinians have been arrested in Gaza, and none have been allowed family or ICRC visits.14 Food supply to Gaza has not been restored to its pre-war figures, and other attempts to bring food to Gaza either by air or by sea have been very partial. The WHO updated its estimates regarding Gaza’s food security to famine.15 The medical aid reaching Gaza is minimal, and Palestinian and foreign doctors report a lack of crucial medication, including anesthetics.16 The upcoming summer months are likely to bring with them further water insecurity and insect-borne diseases. Its neutrality notwithstanding, Cardon’s call for the recognition of our shared humanity holds true today more than ever.

An interview with Christian Cardon de Lichtbuer, January 31, 2024

Can you introduce yourself briefly?

I am currently the International Red Cross (ICRC) Chief Protection Officer. I have worked in the ICRC for 18 years, 12 years in the field, mainly in the Middle East, and almost two years as head of office in Gaza, including during the 2014 escalation. I then worked as the head of mission in Jerusalem, working in Israel and the West Bank.

My starting point is this. I am currently in Geneva, conducting research on the ICRC’s work in the West Bank between January 1949 and April 1950. What we hear about in the news is mostly war casualties, but as a historian of medicine, when I look at Gaza today from afar, I think about sanitary conditions, famine, lack of medical services, and surviving the cold and the rain without proper shelter or dry clothes. I am also thinking about cancer patients, diabetics, and people who need dialysis or even physiotherapy and don’t have access to this. What do you know about the conditions in Gaza in this respect?

A first remark is that it is always impossible to compare war situations. We do not put a hierarchy in human suffering, even if we are very often pressured to support one side or the other, denounce, and blame one party or the other. We are humanitarians, not politicians.

What I am hearing from my colleagues and communities in Gaza and in Israel is that there is a situation of “agony” on both sides. On both sides, you have – among so many other worrying matters – parents who are just dying of deep anxiety and stress. I am regularly in touch with former Gazan colleagues and friends who are telling me that in the last three months, they have been displaced three times, leaving close relatives behind, not knowing if they are alive or dead, and now facing a situation of major humanitarian crisis with unprecedented overcrowding. On the other side, I am hearing from Israeli colleagues and friends the immense suffering of an entire society still literally under shock and so many families still wondering if they will ever again see their loved ones who were taken hostage more than 100 days and never-ending 100 nights ago… And this continues. And this worsens. These situations, on whichever side of the front line, are inhumane and simply unacceptable.

Let me try to give you a glimpse of what is happening in Gaza and what we do not necessarily hear about. Hundreds of thousands of people have been forced to find refuge in shelters, hospitals, schools, at homes of relatives, or sleep in their cars or out in the open after their homes and neighborhoods have been turned into rubble. In the Rafah governorate, you had, before October 7, over 300,000 people. Now, most of the population, 1.6 million, are taking refuge there. Even before October 7, we know that the Gaza Strip was a very densely populated area, but currently, in the South, people are everywhere. Everywhere. The overcrowding is indeed reaching alarming levels. You have the remaining buildings and tents that are being set up outside all around. Streets are full of people, preventing almost any movement. Colleagues and friends tell me they suddenly live with hundreds of people in the same place, which also has a negative impact on their own family, creating tensions, violence, and, in some cases, separations …

Let’s be clear: when it comes to Gaza in particular, we have not moved from a normal situation to a complex humanitarian one. We have moved from an already extremely fragile situation into what can be today described as a humanitarian disaster. Full stop. In addition to all that, the fighting continues at very high intensity during the day and during the night, including where it is supposed to be “safe.” Children are terrified, and this entire generation will be scarred for life.

What does the ICRC see in terms of hunger or even famine?

Very limited food is coming in. In 2014, I had regular interactions with the Israeli Defense Forces’ Civil Liaison Administration. There was always a clear red line. Any hostilities taking place in Gaza, “the lifeline should be maintained, and Kerem Shalom should be open.” There were moments where, for certain hours, it was stopped, and trucks could not get in for security reasons, which you can understand happened, unfortunately. But in general, it was clear that the lifeline had to be maintained. And now, the first decision taken at the very beginning of this war was to almost completely cut this lifeline. To give you some figures: before the war, 500 trucks were coming in daily. On the best days, during the simultaneous release of hostages and detainees, the maximum was 200. Less than half of what you had before and the needs have probably been multiplied by ten. Since October 7, no bakeries have been working due to the lack of fuel, water, and wheat flour and to extensive damage from hostilities.

The first impact is that the prices increased significantly, and the vast majority struggle to pay for food. For example, one egg in Rafah today costs one US dollar. Another example is that in the North, people started making bread from animal flour ... This will have a severe impact on their health.

In addition, in 2014, you still had a bit of agriculture in some parts of the Gaza Strip, mainly in the border area. All this has now been destroyed. Families struggle to find even the most basic food. Parents sacrifice their own meals to feed their children. Should this difficult access to food continue, it will very negatively impact the health of thousands in Gaza, starting with children and the most fragile – the elderly, disabled, pregnant women, and those immunosuppressed.

There is nothing like a well-organized humanitarian response because the continuation of hostilities makes it impossible – whether it is a risk of bombing in the area or looting of our cars because people are just starving. Indeed, security risks come not only from the fighting but also sometimes from inside an exhausted and starving population. What I hear from colleagues are things I have not heard before. Sometimes, humanitarians would, for example, have no other choice than to evacuate distribution sites because of such insecurity.

Following the 1948 war, the major hospitals in Mandate Palestine were left on the Israeli side, and in the West Bank, there were only two small hospitals, in Hebron and Nablus. I understand that today, in Gaza, hospital services are extremely compromised.

The overall health system is in survival mode, unable to cope with the high demands of the wounded and sick. There are still three hospitals functioning, and probably in the coming days, only two hospitals for a population of 2.3 million. These are facts, and this is catastrophic. Think about where you live and how many hospitals are functioning around you. Think about how many relatives you have who are currently being treated for a specific disease. Anything close to this has simply disappeared in Gaza. The only focus today is on “saving lives” and emergency response. Nothing more.

Two ICRC war surgery teams are treating war-wounded patients in the European Gaza Hospital. They treat patients with severe injuries that require complex medical interventions. Even there, essential supplies, like dressing material, are running dangerously low.

Are hospitals and medical personnel targeted?

Healthcare workers and infrastructures are clearly in danger in Gaza. This has unfortunately been the case since day one, and it continues.

We will never stop repeating it, loud and clear: both parties should take all precautions when conducting an attack close to a hospital or medical workers. Hospitals and ambulances should be respected. The law of war is crystal clear: hospitals should be spared and protected at all times. We acknowledge how challenging it is to fight in a densely populated area, but that’s the environment they are in, and they have to act according to the law, both Israel and Hamas.

In current battlefields – and Gaza is no exception – International humanitarian law (IHL) basic principles of proportionality, precaution, and distinction are unfortunately too often being challenged. This is also why we need to maintain a constant dialogue with the parties to a conflict, reminding them of their obligations and bringing to their attention issues of concern related to the respect of IHL we are witnessing in the field.

In 1949, a major concern was epidemic outbreaks. The ICRC worried about typhus, dysentery, malaria, and even cholera. What are your concerns in this regard?

Lack of access to safe water and sanitation creates a serious risk of diseases like diarrhea, dysentery, hepatitis A, and typhoid. Colleagues tell me that all the water-related diseases are either already present or almost present. Yesterday, colleagues were telling me that now we fear that there could be a spread of cholera and other worrying diseases in Gaza. Primary healthcare centers are already overstretched and lacking medical supplies, and the vast majority of patients will go untreated. We are not talking about future consequences but immediate ones.

What about the provision of health to internal refugees? In 1949, there were small ICRC clinics and weekly doctor visits in the refugee camps. Is there anybody working with those who do not get to the hospitals?

Everything related to primary health care, chronic disease, and so on is almost not addressed anymore. The first and top priority is saving lives in the surgical blocks. The vast majority of health workers, whether national or international, are already overwhelmed by the emergency situation, and the rest are being neglected. There are tens of thousands of people who need medical treatment or services not currently available in Gaza, including for cancer, cardiac surgical cases, chronic diseases, etc. What we know from the number of patients in hospitals today is that all those who cannot get to the hospital are probably inside their tents, not treated, under cold and rainy weather… and some might be dying from other diseases ...

What is the role of the ICRC?

We are active on various fronts. This goes from supporting Gazan hospital staff by sending in surgical teams to facilitating the work of water and electricity local actors in fixing infrastructures that have been destroyed. We also play the role of neutral intermediary, which, for example, helps facilitate the simultaneous release of detainees and hostages. I believe that our added value is also linked to the fact that we talk to everybody, and in this case, we remind Hamas and Israeli authorities – as well as the states supporting them – of their legal obligations. We do this 24/7, and this will continue as much as needed.

We also have a key role to play in issues related to the detainees and hostages. This is a major challenge for us in the current environment.

Before October 7, that was one of the biggest ICRC programs in the country: visiting thousands of Palestinian detainees, ensuring they are detained in appropriate conditions and treated correctly, ensuring they can maintain a communication link with their relatives in the West Bank and in Gaza. This activity was unfortunately suspended on October 7, and since then, and despite the fact that thousands were arrested in the meantime, not a single ICRC visit has taken place.

In Gaza, as you know, we could very unfortunately not yet visit the Israeli hostages. We have been very clear since day one that people should, first and foremost, not be taken hostages and that Hamas should release all of them immediately and without conditions. We have repeated this message repeatedly, including in the public domain.

Beyond what parties should respect during a conflict and the access the ICRC should be granted, as an ICRC delegate, not being able to visit the people detained and taken hostage in the middle of hostilities is the source of deep frustration and even anger. We are well conscious that no one really understands how much we try, 24/7, by all possible means of influence, to be granted this access. As always, and wherever we work, we are persistent and will continue pressuring, by all possible means, until we get tangible results.

Another key aspect is related to the conduct of hostility. So, the ICRC, behind the scenes, 24/7, interacts with both parties and any other party who could have an influence. The situation today deserves much more “political action,” not only from the parties concerned, but from the states supporting, advising, and influencing the parties to this conflict because of the role they also have to play as parties to the Geneva Convention: “respect International Humanitarian Law and ensure respect.”

Then, we have a more concrete humanitarian role. We are involved in health, water and sanitation, economic security, and food assistance. We work with local actors, in particular the Palestine Red Crescent Society (PRCS). We are, for example, now, with the ICRC presence, facilitating the reparation of some water pump or some electricity line that have been destroyed as a consequence of the hostilities. Sometimes, we fix a pipe or a line that can re-give thousands of people access to water and electricity. Although these days the movements are so complicated because of the security situation, this is what we are aiming to do more.

Regarding health, we have, and this is a drop in the ocean, two surgical teams working in Gaza. Their work is to ensure a rotating shift with the team still working there. Doctors and surgeons are afraid to move in and out of this hospital for fear of being targeted and working in these conditions. People are constantly coming in, and internally displaced people seek refuge close to hospitals.

Another very serious issue today in Gaza is linked to all the human remains that are still under the rubble and, in consequence, the persons missing or unaccounted for. First, there is always a concern regarding the possible consequences this could have on health and sanitary conditions. Second is the psychological part of not having had the possibility to bury and mourn your loved ones. That is really a field where we have expertise. What we are discussing now with authorities on both sides is that we need access not only to bring in food or medicines and restore water access, but we also need access to support the civil defense, or what remains of it, to remove the rubble, take the bodies out, support identification and in the end making sure families can do their mourning. And that’s a very important element that we have seen in other places and which has consequences for the very long term. From experience, when communities are not able to bury and mourn, and this is obviously the case for both Palestinians and Israelis, the sentiment lingers for years and will prevent efforts of future reconciliation and dialogue.

Finally, a major problem today is that the battle does not stop. The moment you can start moving, you can start thinking and being “ambitious” about the humanitarian response. If the parties and the states influencing them manage to push for more aid to come in and for a truce in the hostilities, then humanitarians, including ICRC, will kick in. We’re getting ready for a massive response. If we have the green light, we could do indeed much more. It is just urgent to rebuild. Starting with rebuilding life. To rebuild vital infrastructures. To rebuild education. To rebuild families and, maybe, one day, also to rebuild a glimpse of hope ... There is no time to lose, and humanitarians will only be able to make a difference if and only if political and armed actors show courage, leadership, and sincere commitment to a viable future, putting an end to this untenable “agony” ICRC and many other humanitarians are witnessing, on both sides and for far too long.

- 1. Bakhir ba-tzlav ha-adom: nukhal le-hashpi‘a be-emet rak kshe-tistayem ha-lehima, (in Hebrew; An ICRC official: We can truly make a difference once the war ends), in: Local Call, 7.2.2024 (https://t1p.de/5yvna).

- 2. On the formation of the refugee problem see Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, 2nd ed., New York 2004.

- 3. Josh Ruebner, Israel is threatening a second Nakba – but it’s already happening, in: The Hill, 17.11.2024 (https://thehill.com/opinion/international/4313276-israel-is-threatening-a-second-nakba-but-its-already-happening/); Bashir Abu-Maneh, Israel Can’t Win Peace Militarily. Palestinian Democracy Is the Solution, in: Jacobin, 14.11.2024; for Israeli Nakba discourse already in early 2023, see Leena Dallasheh, The Normalisation of Transfer Ideology among the Israeli Right, May 2023, Ofek (https://www.ofekcenter.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/The-Normalisation-of-Transfer-Ideology-among-the-Israeli-Right.docx.pdf).

- 4. Greg Myre and Aya Batrawy, Why Egypt won't allow vulnerable Palestinians across its border, in: NPR, 26.2.2024 (https://www.npr.org/2024/02/26/1232826942/rafah-gaza-palestinians-egypt-border).

- 5. International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Report on General Activities (July 1, 1947 – December 31, 1948), Geneva 1949, p. 111–116; idem, Rapport general d’activité du commissariat pour l’aide aux réfugiés en Palestine (1er janvier au 31 mai 1949), Geneva 1949, 1–5; Dr. Hans Mooser, Report on the State of Health and Living Condition of the Palestinian Refugees, 1.10.1948, 476/1/9, Anti-Epidemic Action: Assistance to Refugees from Palestine: General Correspondence, WHO Archives (WA).

- 6. On these organizations’ early work see Catherine Rey-Schyrr, The CICR and assistance for Palestinian Arab refugees (1948–1950), in: International Review of the Red Cross 83, No. 843 (2001), p. 739–762; Julie Peteet, Landscape of Hope and Despair: Palestinian Refugee Camps, Philadelphia 2009; Ilana Feldman, Life Lived in Relief: Humanitarian Predicaments and Palestinian Refugee Politics, Berkeley, CA 2018; Anne Irfan, Refuge and Resistance: Palestinians and the International Refugee System, New York 2023. The United Nations Relief and Work Agency (UNRWA) replaced these organizations in May 1950.

- 7. Commissariat of the International Committee of the Red Cross for Relief to Palestinian Refugees, General Activities of the Medical Service, Geneva 1950, p. 90–126.

- 8. “Barely a drop to drink”: children in the Gaza Strip do not access 90 percent of their normal water use, in: UNICEF Press Releases, 20.12.2023 (https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/barely-drop-drink-children-gaza-strip-do-not-access-90-cent-their-normal-water-use); UN says waterborne illnesses spread in Gaza due to heat, unsafe water, in: Reuters, 12.4.2024 (https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/un-says-waterborne-illnesses-spread-gaza-due-heat-unsafe-water-2024-04-12/#:~:text=Contaminated%20water%20and%20poor%20sanitation,to%20the%20World%20Health%20 Organization); Kayleen Devlin, Maryam Ahmed, Daniele Palumbo, Half of Gaza water sites damaged or destroyed, BBC satellite data reveals, in: BBC, 9.5.2024 (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-68969239).

- 9. Compte-rendu du rapport présente en séance plénière du CICR, le 19 janvier 1950 par M. le Prof. A. Vannotti sur sa mission en Palestine, BG 059/I/GC-209; Report of the Secretary General on United Nations Relief for Palestinian Refugees, 30.9.1949, 22–27, 54–56, 476/1/9, WHO Archive.

- 10. ICRC, General Report, p. 13–89.

- 11. Six months of war leave Al-Shifa hospital in ruins, WHO mission reports, in: WHO Mission Reports, 6.4.2024 (https://www.who.int/news/item/06-04-2024-six-months-of-war-leave-al-shifa-hospital-in-ruins--who-mission-reports).

- 12. Imogen Foulkes, Israel-Gaza war: The Red Cross's delicate role in hostage crises, in: BBC, 27.11.2023 (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-67520263); Heather Chen, ”In the line of fire”: The crucial, neutral role the Red Cross plays in conflicts, in: CNN, 9.12.2023 (https://edition.cnn.com/2023/12/09/middleeast/red-cross-icrc-humanitarian-history-intl-hnk/index.html).

- 13. Corky Siemaszko, Four more hostages have died in Hamas custody; Israel says more than a third are dead, in: NBC News, 3.6.2024 (https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/four-israeli-hostages-died-hamas-custody-rcna155231).

- 14. Patrick Wintour, Red Cross and Foreign Office to discuss plan to visit Palestinians in Israeli detention, in: The Guardian, 16.5.2024 (https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/may/16/red-cross-uk-foreign-office-palestinians-in-israeli-detention).

- 15. Emma Graham-Harrison, Children die of malnutrition as Rafah operation heightens threat of famine in Gaza, in: The Guardian, 2.6.2024 (https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jun/02/children-die-malnutrition-rafah-famine-gaza-israeli-troops-aid-strip).

- 16. Alice Cuddy, Gaza doctors: ”We leave patients to scream for hours and hours”, in: BBC, 18.2.2024 (https://www. bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-68331988).