The First World War centenary has offered, with the exception of Christopher Clark’s The Sleepwalkers, few surprises. Pretty much everything has been said and there is clearly agreement on many subjects. Last year, however, the question of German war crimes during the march into Belgium and France in the summer of 1914 re-emerged – albeit well after its hundredth anniversary, although with much greater intensity than many of the other debates.

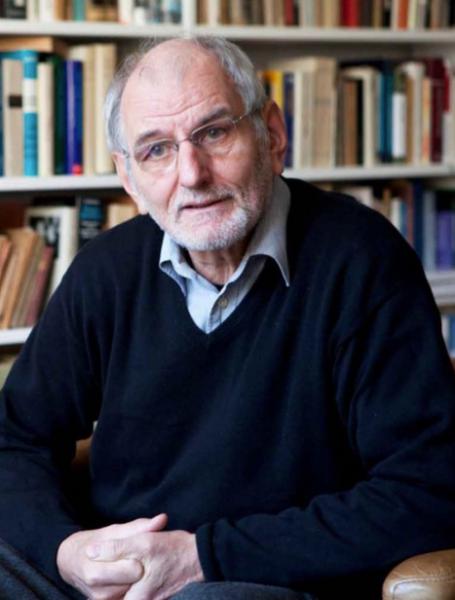

The cause of this controversy was two new publications in Germany which called into question the hitherto internationally accepted historical wisdom. The two Dublin-based historians John Horne and Alan Kramer had presented a milestone in historical research in 2001: German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial. Now a new critique of the theses of this book could be heard: Ulrich Keller, a retired art historian from University of California Santa Barbara published Schuldfragen. Belgischer Untergrundkrieg und deutsche Vergeltung im August 1914. On 27 October 2017, experts met at the University of Potsdam in order to subject the differing positions to a critical examination. Among them was the historian, expert on French history, co-founder and Honorary President of the Arbeitskreis Militärgeschichte, Professor Gerd Krumeich. Markus Pöhlmann met with him. A translation has been provided by Alaric Searle.

Q: On 27 October 2017, you participated in the Workshop "German Atrocities 1914 – Revisited" at the University of Potsdam. Renowned historians discussed German war crimes, their causes and their portrayal at this event. How would you evaluate the conclusions of this meeting? What were your reactions to the discussions which took place there?

A: This workshop in Potsdam was an initial, very important step towards clearing up a point of considerable controversy. It demonstrated that a group of international experts were actually quite open to the research conducted by Ulrich Keller. Through Schuldfragen, he has presented an arresting new interpretation. Nonetheless, in the case of John Horne and Alan Kramer, who had published the standard work on the subject and who were present at the workshop, I noticed a degree of resistance, infused with rather superfluous irony. Horne and Kramer have defended their account in a determined fashion, one could say with dogged determination, and have sought to pick holes in Keller’s work. This is understandable as Keller launched the attack in his book with an unfortunate aggressiveness. But this does not alter the fundamental persuasiveness of his research findings. A debate in the style in which it has been conducted this far will not bring understanding any further forward. We do, therefore, need to focus once again of the contents of Keller’s book.

Q: Which aspects of the book were discussed then in Potsdam?

A: What shocked me was, above all, the statement by Alan Kramer that the witness statements of German soldiers, employed by Keller, could not provide in any way a reason to reconsider the central argument in German Atrocities, namely, that the majority of German soldiers had shot at each other. Keller’s argument, that there are numerous indications that there were Belgian civilians and soldiers disguised as civilians who had shot at Germans from ambush positions, was quite simply denied. I am just as before convinced that a fruitful discussion can only take place when these German statements are in the first instance taken as seriously as those statements made by Belgian civilians and officials have thus far been taken seriously by historians.

Q: Because the apparently one-sided treatment of the witness statements was one of the accusations against the authors of German Atrocities?

A: Yes. Precisely this question was also directed at Horne and Kramer during the conference: why in their book were German sources used in conjunction with the word "claimed" when Allied sources were assumed automatically to be authentic? On this point they remained silent. The paper by Larissa Wegner covered her investigation of an incident in the French town Orchies, based on both German and French sources. She arrived at a much more nuanced picture. She pointed out, correctly in my view, that the assumption that the Germans had not acted without reason did not excuse the brutality of their reaction. I found the intelligent contributions of Alexander Watson and Oswald Überegger, which considered crimes on the Eastern and Balkan fronts, extremely interesting. It becomes clear from their work how important it will be in the future to undertake comparative studies on war crimes.

Q: The event did, in fact, lead to some media coverage, which was rather unusual for a conference of this relatively modest size. The news magazine Der Spiegel devoted an entire article to the event in which, you, Professor Krumeich, commented in relatively critical tones about your fellow historians. Your critique went in the direction of that for the reason that inner-European harmony could not be disturbed, it has been considered politically inappropriate to examine critically Belgian responsibility for acts which contravened international law. In this context the article alludes to a "conspiracy of silence among historians". Have you received any reaction to this article?

A: Here I have to make clear that Herr Wiegrefe from Der Spiegel did not conduct an interview with me in any shape or form! He only read my foreword of Keller’s book and there picked out what suited him. I have never spoken or written about a "conspiracy of silence". That is his invention. I protested immediately to the editor, but have received no response. In my foreword I wrote that it is difficult to engage with this subject because one risks by a defence of Keller isolation within one’s own academic community. That has been and indeed still is the case. I fear that I have lost friends and created much indignation. The study of history is sometimes a dangerous business.

Q: The current discussion also seems to have been ignited by a second publication, which tellingly has been written by an academic outsider. I am referring here to Gunter Spraul’s Der Franktireurkrieg 1914. How would you assess this second new publication on this subject?

A: Spraul’s book is, in essence, a 679-page book review of Horne and Kramer. That is a bit over the top. The book is, nonetheless, at the same time valuable for its focus on the regimental histories. Indeed, precisely because he has studied them closely, he can demonstrate that Horne and Kramer have committed a number of factual errors. But the major error committed by Spraul is his lack of interest in the extensive brutality of the German acts of retaliation; this goes so far that especially appalling cases are not even mentioned. He is quite simply not interested in what was unleashed on the Belgians. That is unacceptable!

Q: In the wake of the aforementioned research publications, and following the Potsdam Workshop, the question is naturally whether German Atrocities by John Horne and Alan Kramer should be reassessed. In your opinion what value does the book still possess?

A: Much of the book remains valuable, objectively speaking, and it remains a memorial for the attempt to explain the crimes of 1914 at last in terms of mentalities. Still, the entire unintended bias has to be challenged. It will be important in the future that the German sources be lent the same heuristic value as the Belgian, French and British. Propaganda and lies were to be found on both sides in huge quantities, but attempts to identify the truth as well.

Q: Which research questions are particularly urgent within the context of this particular debate?

A: To be concrete here, I would trust that we would begin to examine whether and in what way the attacks by Belgian civilians were only isolated incidents – which is what Horne and Kramer say – or whether they were undertaken in a collective fashion. Keller’s thesis, that they must have been organised "from the top" appears to me – at present – to be not based sufficiently on enough source material. However, it seems likely that there must have been consultation at local and regional level because the huge number of incidents on many sides cannot be otherwise explained. Furthermore, it would be important to discover why the German soldiers carried out that many appalling "retaliatory actions" beyond the norms and habits of the time. This was not because they were somehow "barbarians", as today still rather simplistically is assumed. On the contrary, crimes of this type and to this degree were never repeated again during the occupation in the West. What was actually going on in August/September 1914?

Q: Young doctoral researchers have, for years, written loyally in support of the theses of their supervisors. Some of these academic teachers and older authors like Keller and Spraul have begun to question some aspects of the accepted wisdom. When I read today Der Große Krieg from 2010, published by yourself and Jean-Jacques Becker, I notice that here aspects of the war are mentioned which are missing from the most recent survey works on the Great War – for instance, the épuration, in other words, the ethnic cleansing of Alsace-Lorraine during and in the aftermath of the First World War. Does the wider debate possibly possess a generational dimension?

A: I don’t know just how "loyal" the younger historians are really, since there are – as before – also those who do not fall into this category. Whether one can describe the expulsion of French and Germans as ethnic cleansing is to me questionable. But setting that aside, there are as always research problems which appear, and others which lose their relevance. When I remember how we argued over the Paris Commune or Bismarck’s Emser telegram in the 1970s, and how the events of 1900 were intertwined with experiences in the Federal Republic and the GDR, it can be seen how time has fortunately left these disputes behind. The question as to whether Bonn could become Weimar is another dispute which no longer interests anyone because no one knows any more where Bonn is, apart from those who live in Bonn. It is impossible to say, though, which questions have definitively laid to rest. I do wish, above all, that many younger and older researchers would not follow the latest trend in terms of subject matter or the choice of words. They should rather research those subjects which interest them, and where they have a question, and where they are not yet satisfied with the answers. I find it sad that we all run after the latest catchwords. At the present juncture, the concept of the "transnational" is extremely important, a couple of years ago the word "sustainability" was the one which was required in order to secure research funding. Conformism and the need to belong to a "school" are the greatest enemies of historical investigation.

Q: Belonging to a school of thought also has to do with academic culture and language. Few historians in past decades have moved within the Franco-German academic field as much as you have. In the case of such controversies can one recommend a specific academic format for such revisiting of established interpretations? Should the latest research findings not be translated more frequently into the other language as has been the case in the past?

A: There are without doubt scholarly cultures which are influenced by national cultures. In France, they are not used to differences of opinion being discussed so openly among friends. Where scholarly disagreements occur, for instance in the case of coming to terms with the history of Vichy, the debates tend to be conditioned more strongly than in Germany by ideological groupings. This normally ends up as Left versus Right. In fact, it is quite difficult to say where the border runs between these two Frances. President Macron is attempting at the moment to introduce a third path between the two. What is certain is that it occurs much less frequently than in Germany that it comes to loud disagreements during a conference. The opposing views tend to be hidden behind subtle, offhand comments. What is difficult is when, for instance, one participates as a German in such internal French debates. A good deal of diplomacy is called for and every possible faux pas can be made if one is not careful.Finally, in terms of the communication in the other language: today younger French researchers are better able to speak German than many of us presume. The year of those who turned up only able to speak French has now gone. Still, translation remains useful whenever it is possible to arrange. Indeed, I would now argue that in Franco-German academic dialogue one should agree to communicate in English since both sides are, in fact, now able to do that.

Zitierempfehlung

War Crimes in Belgium 1914: An Interview with Gerd Krumeich, in: Portal Militärgeschichte, 20. Februar 2017, URL: http://portal-militaergeschichte.de/node/1857

(Bitte fügen Sie in Klammern das Datum des letzten Aufrufs dieser Seite hinzu.)